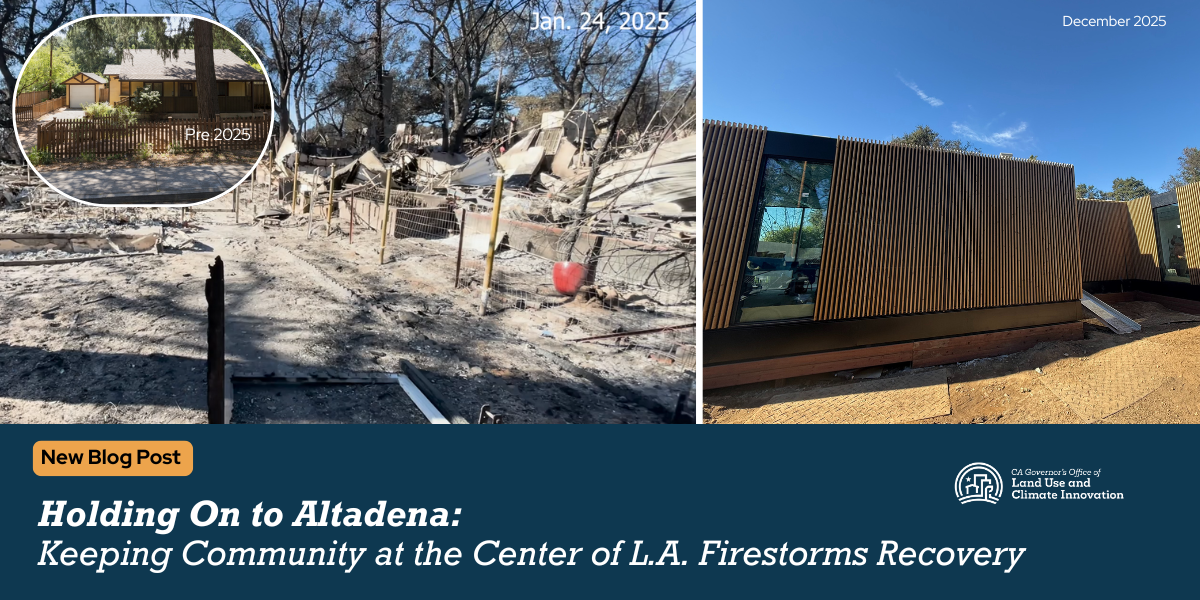

I first met Eaton Fire survivor Steve Gibson in January 2025, just days after the firestorm consumed his beloved, historical Altadena home of more than two decades.

His 1920s-era home was one of 9,000 buildings destroyed in the Altadena inferno, and at least 19 people tragically lost their lives.

In the immediate aftermath of the relentless flames and devastation, I joined colleagues from across the Governor’s Cabinet, the City of Pasadena, and Los Angeles County to meet Altadena residents in their community, hear their stories, and learn from them what support they need.

This wasn’t a one-off visit: For days, weeks and months after the fire, state teams returned again and again, meeting with families who had lost everything. What stayed with me most were the stories—and the responsibility they carried. We took those conversations back to the Governor and they helped shape the state’s response: removing red tape, accelerating permits, and staying focused on what recovery actually looks like for the people living through it.

Steve Gibson was one of those voices.

Despite everything he had lost, he spoke with clarity, optimism, and a deep commitment to his community—and a determination not just to rebuild his home, but to rebuild his entire neighborhood. What struck me immediately was how Steve described his place in Altadena. “I’ve been here 24 years,” he told me, “and I’m still the newcomer.” It was a simple line that said everything about the generations of families who had lived there before him—and what was truly at stake. And yet, even then—less than a week after the devastation—Steve was already clear about one thing. “I want to come back home,” he said. “I don’t know what the permitting process looks like, but I want to rebuild.” Even in those early days, Steve was honest about the emotional toll—and about what it would take to move forward. “Hope doesn’t just happen,” he told me. “You have to decide it. You have to plan it. It’s hard work.”

In the weeks after the fire, Steve and his wife moved between five different hotels. The loss was constant—and so were the reminders. The smell of smoke lingered, triggering memories and grief when they least expected it. “At night, we’d reach for things that were no longer there,” he said. “That actually no longer even existed.” Steve doesn’t pretend recovery happens on its own. He talks openly about trauma—and the work it takes to move through it. Both he and his wife sought therapy through UCLA’s post-fire support program, taking part in one-on-one virtual sessions designed to help fire survivors process loss. That willingness to name the difficulty—and still choose a path forward—was striking.

Altadena is not just a neighborhood. It is a place with deep roots and a long history as a Black community—a place built by families who fought for stability, homeownership, and belonging when those opportunities were far from guaranteed. Preserving that history means ensuring longtime residents like Steve are able to return—not displaced by disaster, rising costs, or a recovery system stacked against them. Steve had lived in Altadena for 24 years. Leaving wasn’t an option he was ready to accept.

A year after the Eaton Fire, I met Steve back at the site of his home. My first instinct was to ask the most basic—and heaviest—question: “How are you doing?” It’s a question we often ask out of habit. But in that moment, Steve’s response carried the full weight of what he and his wife had been through. “Can I say, conflicted?” Steve answered. Relief alongside grief, momentum alongside reality. With construction on his new home nearly complete and a move-in date ahead for Steve — the reality is many of his neighbors are still navigating their own uncertain paths home. According to Steve, some neighbors are still stuck in the permitting process. Others are trying to manage the process themselves—working with architects, hiring contractors piece by piece—only to find delays and rising costs at every turn. “We made the decision knowing we didn’t have enough money to rebuild,” Steve told me. “But we decided to go forward anyway.”

Like so many families after disaster, Steve and his wife quickly learned that insurance alone wouldn’t be enough. “That’s the elephant in the room for Altadena,” Steve said. “Most people don’t have enough money to rebuild. That’s why they’re waiting.” Steve is clear-eyed about it. “Permitting adds cost,” he said. “But the biggest issue is money. Prices have gone up for everything—and they’re still going up.” Time matters, too. Traditional contractors told Steve rebuilding could take two or even three years—if everything went right. For families living in temporary housing, that kind of wait can quietly become displacement. That led Steve and his wife to explore factory-built housing. “What really helped us decide was walking through the factory and walking through the house,” Steve said.

They walked through a completed unit right on the factory floor—opening cabinets, stepping into bedrooms, imagining daily life again. At a local factory in Gardena, they toured homes being built piece by piece. They walked through a completed unit right on the factory floor—opening cabinets, stepping into bedrooms, imagining daily life again. They weren’t alone. Other families from Altadena were there too—asking questions, weighing options, trying to see a future after loss. Within weeks, Steve and his wife signed a contract. They moved forward not because it was easy—but because waiting felt impossible. A little more than a year later, Steve is preparing to move back into his Altadena neighborhood. He is the first of his neighbors to do so.

Construction itself took just weeks. Six weeks from foundation to walls, and less than three months to near completion—even after crews had to clear debris, remove tree stumps, and re-grade land left uneven after the fire. Seeing that transformation—standing on this site again—is powerful. A year ago, this was devastation. Now, it’s a new beginning. This milestone brings complicated emotions. “Like I said, conflicted,” Steve shared. “Things are going well, but we’re going to be all alone when we move back.” Relief and grief coexist. Progress doesn’t erase loss. Steve keeps showing up anyway—for neighbors, for gatherings, for conversations that remind people recovery is possible, even when it’s hard. “We’ve talked to our immediate neighbors,” he said. “They all want to rebuild. That’s a positive sign.” His new home is also built with resilience in mind—largely steel, with fire-resistant materials designed to reduce how embers and heat can enter. “Traditional homes have vents where sparks and ash can get in,” Steve explained. “This house is designed to make that much harder.”

Steve doesn’t tell his story to suggest the path is easy. He tells it because it’s real. And while the road ahead for Altadena is long, his return is a powerful signal of what’s possible. “I want to be an example for others,” he said. “We’re almost ready to move back in, so I know it can be done.” Recovery is not just about rebuilding structures. It’s about families coming back. It’s about neighbors seeing someone return and believing they can, too. It’s about honoring the generations who built a place—and ensuring disaster doesn’t erase them from it. Steve’s choice—to stay, to rebuild, to keep showing up—is an act of love for Altadena. And it reminds us that resilience isn’t loud or flashy. Sometimes, it looks like choosing to come home—and helping others believe they can do the same.

A place where belonging is earned through showing up for one another and through a collective commitment to rebuild not just structures, but trust and continuity.

After listening to Steve, this time a year out from the fire, it struck me that when he described himself as a “newcomer” during our first meeting, what he was really describing was a community defined not by tenure, but by care. A place where belonging is earned through showing up for one another and through a collective commitment to rebuild not just structures, but trust and continuity. That outlook reflects the resilience of Californians across the state. From wildfires, floods, and extreme heat to economic shocks and public health crises, Californians have repeatedly faced challenges that test the fabric of our communities. And time and again, people respond the same way Steve did: by leaning into community, by insisting on rebuilding together, and by believing that recovery is possible if it is people-centered.

As LCI continues to support recovery across Los Angeles County, Steve’s words stay with me. They are a reminder that effective recovery is not just about speed or efficiency. It is about honoring local voices, protecting community identity, and matching the optimism and determination of residents with a government that listens, learns, and delivers. That is the responsibility we carry. And it is one we must continue to meet, alongside communities like Altadena, every step of the way.

Keep up with all of our stories at lci.ca.gov and via our monthly newsletter.